This story was first posted to the Indiana Capital Chronicle, indianacapitalchronicle.com

Misinformation, myths and politics have contributed to Indiana’s lack of a cohesive, statewide policy on renewable energy.

Seventy-two of 92 counties have moratoriums or bans on such installations, according to legislative energy head Rep. Ed Soliday, R-Valparaiso. Several attempts this year to intervene against blockages died, but lawmakers are starting to recognize the need for diversification.

“As long as there’s demand for renewables, if we can’t have them here, we’ll buy it from somewhere else – our folks will be paying the transmission costs plus the possibility of more,” said Soliday.

He said organized anti-renewable energy movements travel the state, attending county commissioners’ meetings, adding that they “can be quite unkind, threatening and so forth.”

While debate continues, the price of electricity is rising in Indiana. Once among the lowest in the United States, the state now ranks 28th for cost.

Locals see things differently

Decatur County resident and farm owner Albert Armand emphasized he’s not against solar, but concerned about preserving valuable farmland.

“My view on these solar installations is that there’s a place for them and the best place is not a corn field,” he said. “We have a lot of ground we could use. We can put solar panels on roofs, over parking lots — if we install these on farm ground we’re going to eliminate a lot of crop acres.”

Larry Heger is another Decatur County resident who helps manage a Facebook group — Decatur County Citizens Stop Industrial Solar & Wind — alongside his wife. He described himself as “against solar taking out good-quality farm ground.”

As an elected Republican in a conservative area that votes 78% Republican, we don’t want the green energy stuff in our county.

– Ripley County Commissioner Mark Horstman

Heger’s group is primarily local landowners who, he said “would live across the road from one of the projects” and are “very concerned about their landscape, how it affects their home value.”

He claims he’s encountered “like, less than a dozen” people supportive of renewable energy in Decatur County. Heger believes they’re the landowners “who signed the lease.”

While Decatur County has discussed a solar-specific ordinance, it’s currently under a moratorium. County Commissioner Jeremy Pasel, a Republican, declined to be interviewed.

Nearby Ripley County approved solar energy regulations last year. County Commission President Mark Horstman said the three-person body felt their county needed its own standards.

“We had caught wind that some landowners had signed up for commercial solar and some neighbors were opposed. We realized we were set to have the state solar rules in place, because we didn’t have our own,” he said.

He said the area eyed for solar expansion was in the north part of the county, with a farm and housing development nearby. Horstman is among those who believe such installations lower property values.

“As an elected Republican in a conservative area that votes 78% Republican, we don’t want the green energy stuff in our county,” Horstman continued. “The people that elected me do not want it in our county. On the other side — we don’t have the demographics or topographies for it. We don’t have vast lots of land in our area.”

“So, you’re basically telling somebody – your biggest investment you’re ever going to make, your home, now you’re going to look at solar panels across the street,” he said, citing a belief that the panels lower surrounding property values. “I’m not opposed if they want to put a 1,000 acre solar farm in the middle of 5,000 acres and two people live there, that’s fine, but we don’t have that type of area in Ripley County.”

Ripley County’s ordinance, Horstman believes, gives landowners room to negotiate while still requiring specific setback distances.

“I understand people have rights to do what they want on their land, but you don’t have a right to put confined feeding in a residential area, there’s rules in place,” and renewable energy should be handled similarly, he said.

He said he personally felt the ordinance should be more stringent but the three commissioners negotiated a compromise.

Future of renewables

Indiana Citizens Action Coalition Executive Director Kerwin Olson thinks these types of ordinances are holding Indiana back.

“We can’t seem to get legislation passed in any way, shape or form to encourage or incentivize clean, renewable energy,” he said. “Economics and technology are certainly not standing in the way. The barriers are political, and the barriers are the will to move away” from non-renewables.

“Of course, the utilities themselves and the fossil fuel industry — they have enormous influence in Congress and statehouses across the country,” he continued.

Olson and other renewable advocates say Indiana needs to diversify its energy portfolio to both reduce prices and eliminate fossil fuels. Several have pointed to White County as a leader.

The county currently has commercial wind and solar facilities, plus hydroelectric dams.

Its exploration of commercial wind began in 2007. Leaders reviewed ordinances and added language where needed.

But, “it wasn’t really the county that was pursuing this,” Republican Commission President Mike Smolek said. “It was the local farmers that were pursuing this.”

“The commissioners before me did their due diligence,” continued Smolek. “They went to California, Arizona, Texas” to see how renewable energy worked in those areas and what could be done to enhance road use agreements and other items.”

My biggest fight these last couple years has been fear and Facebook.

– White County Commissioner Mike Smolek

The county’s first commercial wind facility launched in 2008. The county approved the construction of a large-scale commercial solar facility in September 2024, according to WFLI.

But resistance to commercial solar and battery storage — plus, plenty of myths and misconceptions — has surged in recent years, per Smolek.

“My biggest fight these last couple years has been fear and Facebook,” he said.

“You don’t, as a normal, general citizen, get to see these things in operation, don’t understand it — they don’t know what’s going on,” he added. “And then you get people on Facebook that talk about stuff they don’t really know about. Trying to get everybody on the same page, (give them) the knowledge that you know and teach them about it is a big thing.”

The prospect of small modular nuclear reactors have also prompted anxiety, Smolek said.

White County Commissioner Mike Smolek

“It’s human nature to be afraid,” Smolek said. “All we can do is educate ourselves and figure out what’s best for us. The deciding factor is, we know we need power. Everybody depends on it. Every manufacturer, every household, every business all depends on this same grid.”

That’s among Olson’s top two reasons why he says rural communities should consider renewable installations: Indiana’s currently an energy importer.

“There’s absolutely no reason we don’t want to build more energy in-state and be energy independent. That’s good for everybody – it brings down prices,” and lowers consumers’ electric bills, he continued.

With renewable energy, Olson said, you get an energy source “that is not reliant on a fuel source and all the additional costs and volatility that come along with purchasing coal, purchasing gas, purchasing oil — in the markets, operation and maintenance on the fossil fuel power plants.”

But number one is the revenue.

Renewable energy, he said, provides income for schools, roads, parks and more. It brings jobs to the community.

The other main reason: “We are an importer of energy right now,” Olson said.

“There’s absolutely no reason we don’t want to build more energy in-state and be energy independent. That’s good for everybody – it brings down prices,” and lowers consumers’ electric bills, he continued.

With renewable energy, Olson said, you get an energy source “that is not reliant on a fuel source and all the additional costs and volatility that come along with purchasing coal, purchasing gas, purchasing oil — in the markets, operation and maintenance on the fossil fuel power plants.”

He acknowledged that studies on the impact to property values haven’t been conclusive. But he dismissed concerns about soil and farmland as “completely junk science — if you talk to Farm Bureau, the Purdue (University) agriculture folks.”

“Nobody … is saying we’re going to be 100% wind or 100% solar,” he continued.

“When you invest — you want a diverse portfolio. We (similarly) want a combination of all resources to ensure reliability, ensure resiliency to shelter ratepayers from the risk of being reliant on one source alone.”

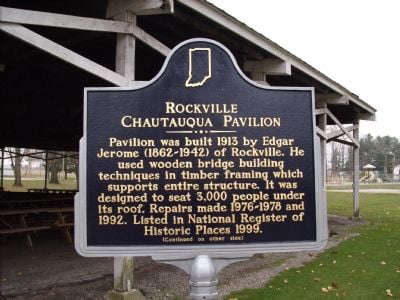

Rockville Parks Board continues working on quality of life improvements

Rockville Parks Board continues working on quality of life improvements

Indiana advances coal ash permitting program

Indiana advances coal ash permitting program

Indiana's state parks offer New Years Day events

Indiana's state parks offer New Years Day events

Rockville Council strips Clerk-Treasurer of Town Manager duties

Rockville Council strips Clerk-Treasurer of Town Manager duties

DNR receives regional award for project on former mine land near Pleasantville

DNR receives regional award for project on former mine land near Pleasantville

ISP shopping safety tips

ISP shopping safety tips

Funding available for waste tire cleanup projects

Funding available for waste tire cleanup projects

Riverton Parke's Emily Adams awarded the Lilly Endowment Community Scholarship for Parke County

Riverton Parke's Emily Adams awarded the Lilly Endowment Community Scholarship for Parke County

BMV announces Christmas and New Year's Day holiday hours

BMV announces Christmas and New Year's Day holiday hours

Indiana launches Smart SNAP

Indiana launches Smart SNAP

Indiana 211: Connecting Hoosiers to holiday support and essential resources

Indiana 211: Connecting Hoosiers to holiday support and essential resources

Department of Homeland Security launches Worst of the Worst website

Department of Homeland Security launches Worst of the Worst website

Governor Braun takes action to waive hours-of-service regulations for transporting propane

Governor Braun takes action to waive hours-of-service regulations for transporting propane

Two Indiana State Fair Commission executives elected to prominent national IAFE Positions, Indiana State Fair honored with multiple awards

Two Indiana State Fair Commission executives elected to prominent national IAFE Positions, Indiana State Fair honored with multiple awards

Cover Crop Premium Discount Program available for Hoosier farmers, new pre-enrollment available

Cover Crop Premium Discount Program available for Hoosier farmers, new pre-enrollment available

Indiana FSSA extends open enrollment for HIP and PathWays Plans through December 24

Indiana FSSA extends open enrollment for HIP and PathWays Plans through December 24

Consumer Alert: Dozens of dangerous products recalled in November

Consumer Alert: Dozens of dangerous products recalled in November

Connect with Indiana 211 to find local warming centers during the winter weather season

Connect with Indiana 211 to find local warming centers during the winter weather season

Car crash claims Greencastle life

Car crash claims Greencastle life